Here is the first article of the “Ant Section” by Théophile. Set out to discover ants…

Ants are what are known as eusocial hymenopterans forming the family Formicidae.

But what does all that mean? Let’s trace back their phylogenetic tree to better understand what they are!

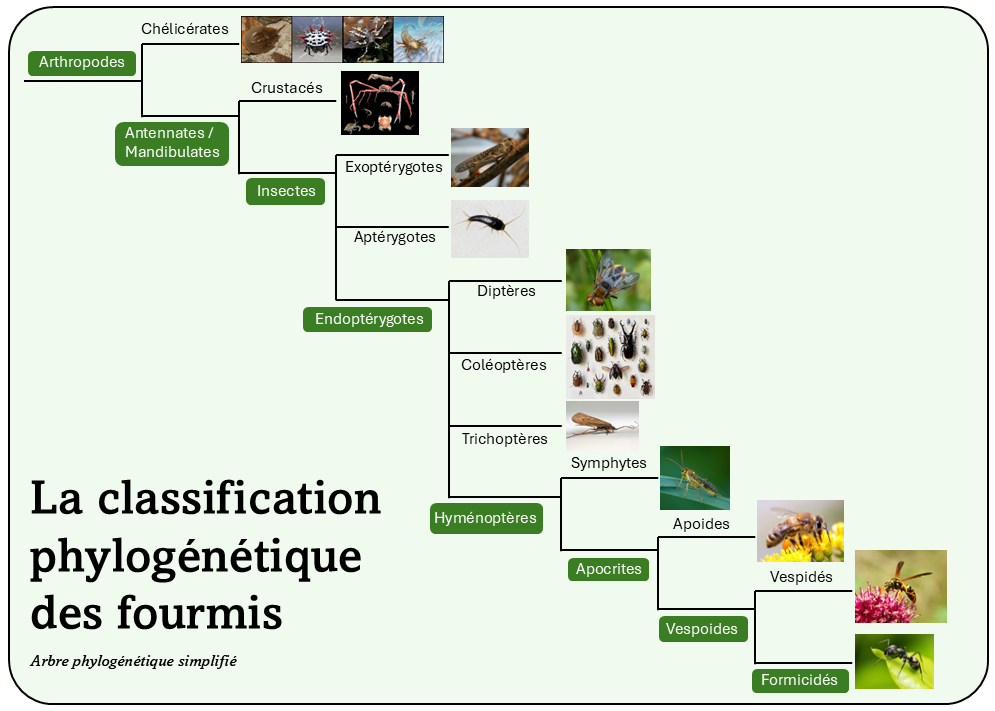

The Phylogeny of Ants

Phylum: Arthropoda

Arthropods are animals characterized by their segmented bodies, often with specialized segments (this is called heteronomous metamerism). Their bodies are covered by a rigid cuticle, forming a kind of exoskeleton. They possess an exoskeleton and jointed appendages.

This phylum includes many well-known groups, such as:

- Crustaceans (crabs, shrimps, etc.)

- Arachnids (spiders, scorpions, etc.)

- Myriapods (millipedes, centipedes, etc.)

- And of course, Insects!

Class: Insecta

Insects have segmented bodies divided into three parts: head, thorax, and abdomen. They have a chitin-based cuticle (a molecule that gives rigidity), pierced with spiracles leading to a tracheal respiratory system. They also possess three pairs of legs and, in most species, one or two pairs of wings.

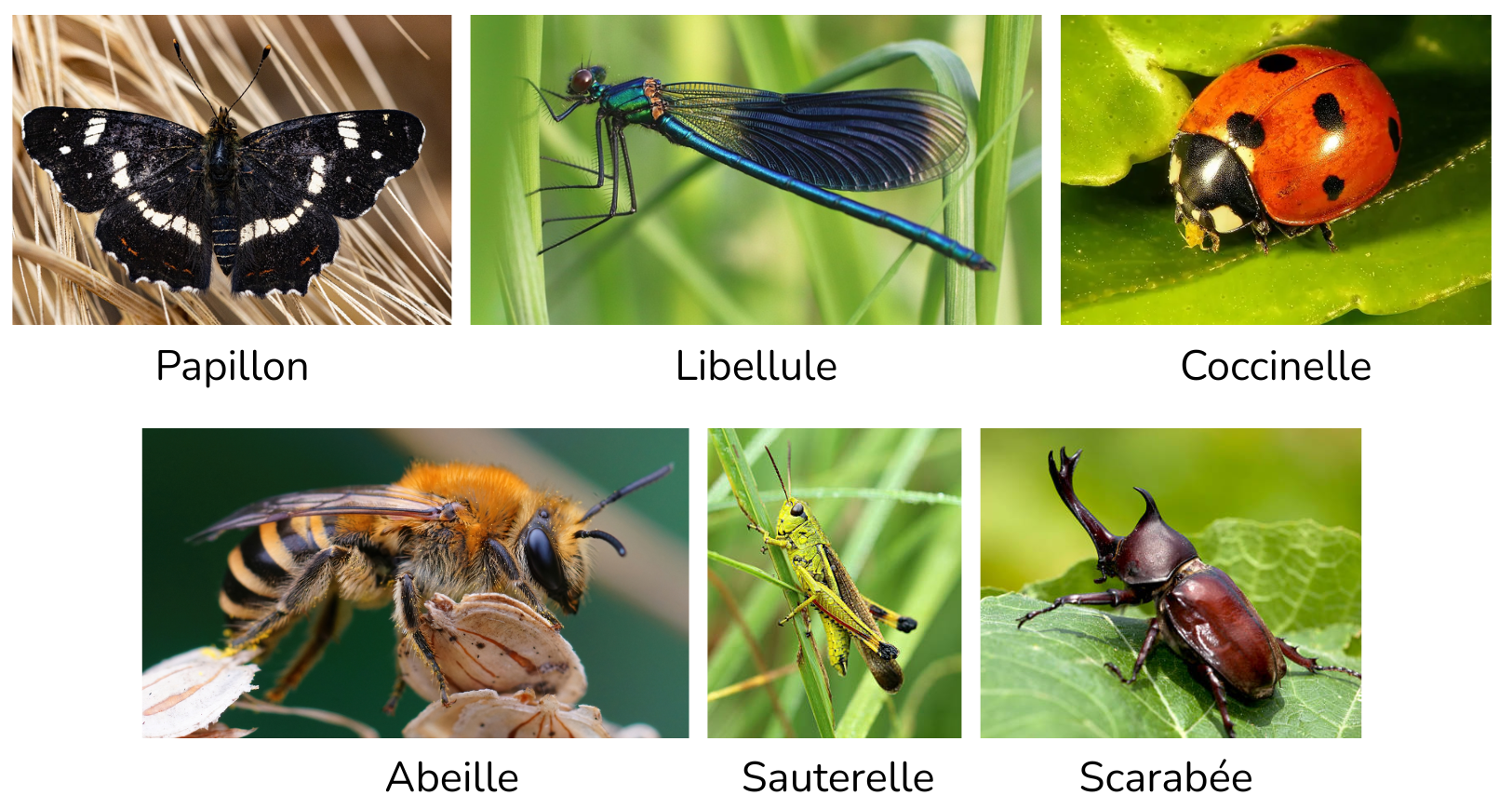

This class includes a tremendous diversity, notably:

- Lepidoptera (butterflies)

- Orthoptera (grasshoppers, crickets, etc.)

- Coleoptera (ladybugs, beetles, etc.)

- Odonata (dragonflies)

- And Hymenoptera…

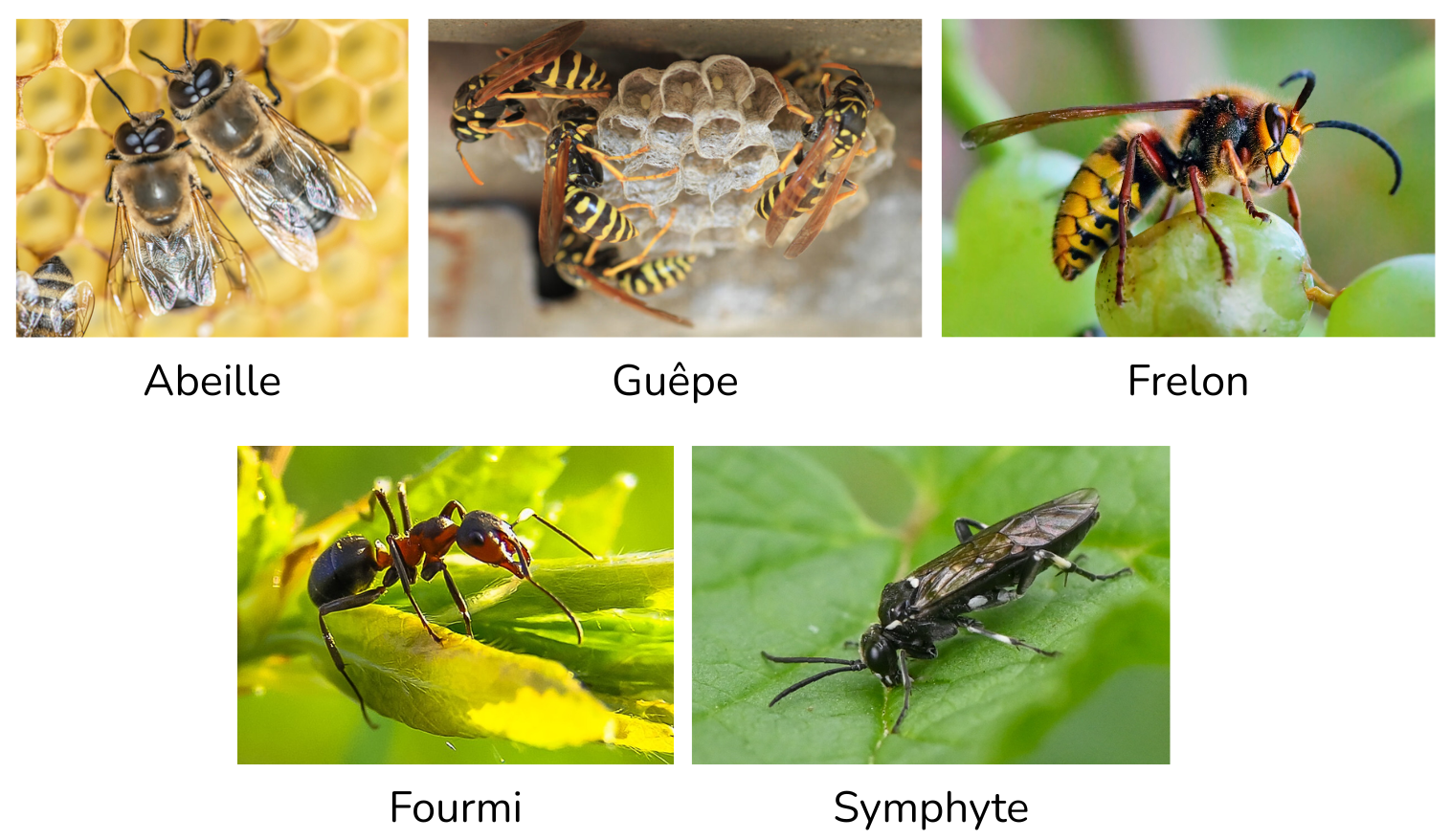

Order: Hymenoptera

Hymenopterans are characterized by two pairs of membranous wings, with the forewings larger than the hindwings. They also show genetic dimorphism, meaning that males and females are genetically different. Males are haploid (from unfertilized eggs, with a single set of chromosomes), while females are diploid. Their thorax, especially the second segment (mesothorax), is highly developed to support flight muscles.

This order includes highly social species like bees (Apidae), wasps (Vespidae), hornets, and of course, ants.

Family: Formicidae

Ants are strictly eusocial insects, which means there are no solitary ant species, unlike some bees or wasps.

Currently, around 16,000 species have been described, but scientists estimate there may be between 25,000 and 40,000 species.

Thanks to their remarkable social organization, adaptability, and division of labor, ants have colonized almost all terrestrial environments—except Greenland, Antarctica, and a few remote oceanic islands.

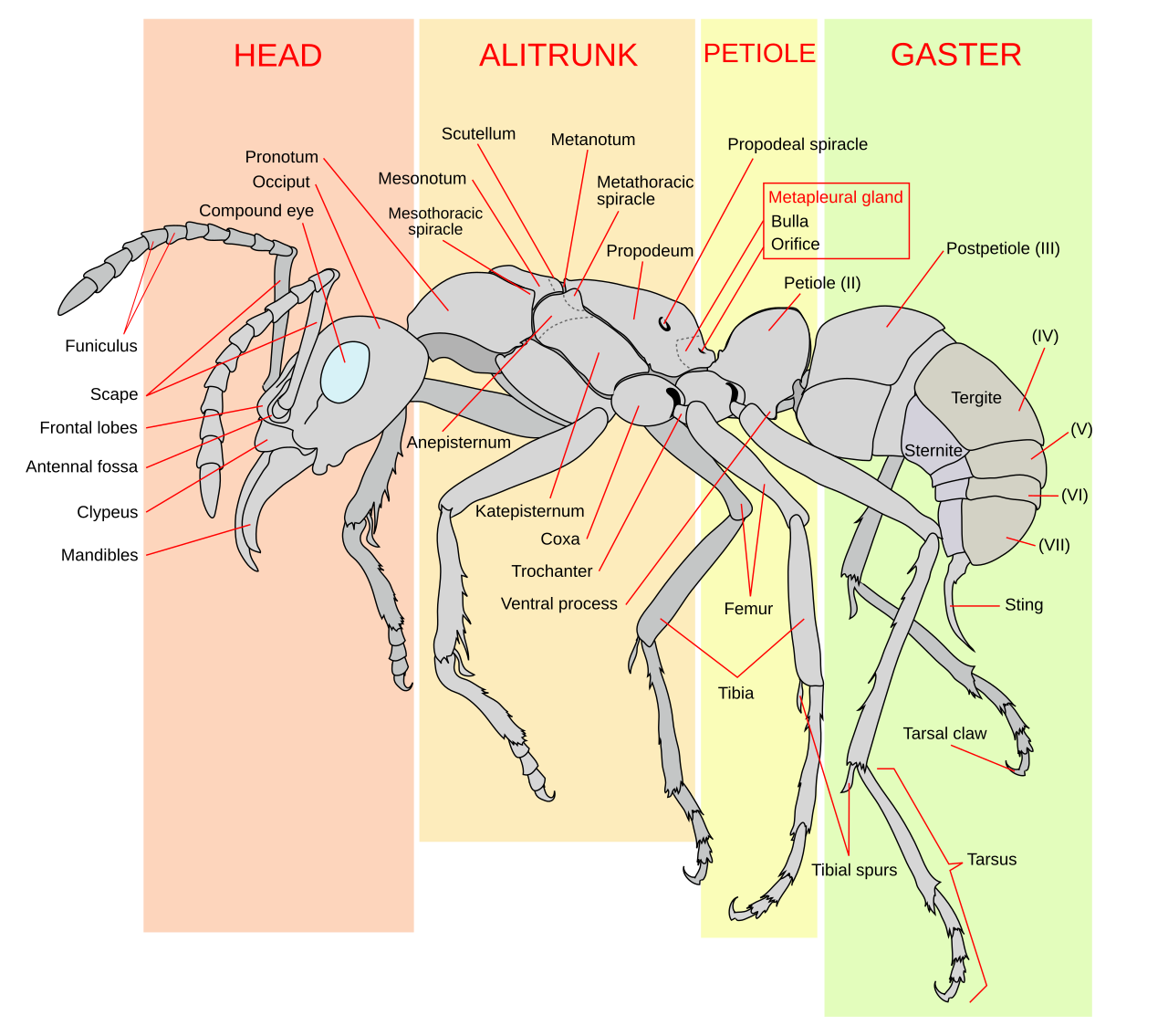

As apocritan hymenopterans (a suborder marked by a constriction between thorax and abdomen), ants have a body divided into:

- Head

- Thorax (or mesosoma in ants)

- Petiole (narrow segment(s) connecting thorax and abdomen)

- Gaster (the true abdomen)

This body segmentation is linked to their lifestyle and specialization within the colony.

Ants: Structurally and Behaviorally Diverse – An Introduction with Size Polymorphism Among Workers

Most ant species show strong intraspecific polymorphism, with marked differences between colony members, especially between queens and workers. In some genera, such as Camponotus and Atta, this polymorphism extends to the workers, who fall into several morphologically and functionally distinct castes:

- Majors, usually in charge of defense and tasks requiring strength;

- Medias, versatile;

- Minors, smaller, handling delicate tasks and nest maintenance.

In the genus Atta, known for fungal agriculture, caste-function distribution is particularly evident. Majors cut leaf fragments and, along with medias, carry them to the nest. Minors maintain the fungal cultures, removing debris and tending the mycelium. These ants don’t eat the leaves but feed on the symbiotic fungus grown on them.

Social polymorphism in Atta cephalotes with 7 workers (representing 3 castes) on the left and 2 queens on the right.

Atta workers from different castes bringing leaves and maintaining fungus gardens.

In Pheidole pallidula (see photo below), a clear worker dimorphism is observed: majors and minors. Majors, with oversized and hardened heads, act mainly as soldiers defending the nest and food zones. Minors handle most daily tasks—food gathering, brood care, nest upkeep. P. pallidula has an omnivorous and opportunistic diet: sugary substances (fallen fruits, aphid honeydew) and small invertebrate prey.

Two workers and one major (center) of Pheidole pallidula

Two workers and one major (center) of Pheidole pallidula

In Messor barbarus (see below), workers are also divided into castes, with majors easily recognized by their large dark red heads, housing strong mandible muscles. Unlike the classic soldier role, these majors specialize in seed crushing, the main colony food source. The genus Messor practices a primitive form of agriculture, producing “ant bread” from crushed seeds and saliva. The genus name comes from Latin messōris (harvester). Interestingly, despite their huge mandibles, M. barbarus majors are described as shy and non-aggressive. They focus on seed processing and storage, while defense is handled by medias and minors in emergencies—showing that major caste morphology doesn’t always imply a fighting role.

Messor barbarus: 4 minors on the right, 2 majors (big red heads), and 1 media in the background.

Messor barbarus: 4 minors on the right, 2 majors (big red heads), and 1 media in the background.

These examples of functional polymorphism lead us to a new question: what do ants actually eat? Between fungus growers, seed crushers, fruit foragers, and insect scavengers, the dietary spectrum of ants is remarkably diverse.

This diversity reflects ants’ extraordinary ecological adaptability, driving their evolutionary success and group diversification. Unlike honeybees (nectar-based diet) or termites (dead plant matter), ants show incredible dietary flexibility. Most species are opportunistic omnivores, consuming both plant and animal resources. Some are highly specialized in precise ecological niches.

As you’ll see in this blog, exceptions and variations exist at all levels—social structure, defense strategies, reproduction… and diets. It’s this very diversity that makes ants so fascinating to observe and study. If these few examples intrigued you, wait until you discover the incredible variety of strategies ants have evolved—dietary, social, reproductive, defensive, and more—which we’ll explore together in future blog entries.

Key Takeaways

Here is a simplified phylogenetic classification tree of ants: